I’m 57 years old. It’s worth starting with that because that’s how long, at least approximately, it took me to know something that happened when I was only eight months old. It took this long for me to unwrap a family secret had been buried except for a comment that my older sister made years ago, that was disregarded but remained waiting to be picked up again so that it could be broken wide open.

This story is about death and disability. It’s about how we perceive ourselves through bad things, and how that perception ripples through relationships and time. Its about religion and judgement, and grace.

Part 1: Family

One of my youngest memories is of my oldest sister, who had a habit of sitting on the couch in our living room and constantly rocking back and forth. I didn’t know this was a type of self-stimulation, or “stimming” behavior. She was withdrawn, and often had trouble with social interactions, but she was also beautiful and my big sister. She had a “flat” way of speaking and was typically very direct. She didn’t understand humor at times, and this would often result in some sort of fight or argument. I didn’t know what autism or ADHD was. She was just my sister.

As we grew up, my older brother and sister were constantly fighting. It was a never-ending squabble between the two of them because of an action my sister took, or because my brother expected to be the authority over the rest of us. I tried to be a peacekeeper and regularly failed, or ended up in my own altercation with my brother. We fought like siblings and we stuck together like siblings.

My younger brother was born, and my two youngest sisters were born almost exactly two years apart to the day. They looked so much alike that they were often confused as twins. They were adorable together, and shared the status of youngest in the family. They had the benefit of attention and older siblings. In the grown-up version of ourselves they became the most well-adjusted and social members of our family.

When the girls began to draw, it was noted then that they were writing in mirror-form, like my older brother had done when he was younger. We learned then that this was called dyslexia, and that there were methods to treat it that my older brother did not have the opportunity to be part of. This may have explained his love of the outdoors more, and why he became an avid reader later than I, or my younger brother did.

I’m under the impression that we grew up in the 70’s in very rural spaces that did not have access to the services and medical supports that could have benefited us. My father had always said he wanted to go where there were no sidewalks, and this very much defined our circumstance and place in life growing up.

I would not describe myself as a social butterfly. I had few friends growing up, that I self-explained as being a result of moving several times in my youth. I had (and still have) tendencies to ruminate on thoughts or generally lose myself in thought. I had favorite clothes and dressed in specific ways – and still do. I remember being taken out of class in middle school to have a Counselor test me using questions on social situations and how I felt about them. I can say with confidence that my family had a lot of neuro-divergence that was unrecognized for what it was. As an adult I struggle with the idea that I could have been diagnosed at a younger age but am too masked and am just “normal”.

In high school, my oldest sister started a pattern of behavior that was at first rebellion, then recognized as symptoms of mental illness. Her world had already begun collapsing in 1981, when my mother was diagnosed with a particularly aggressive form of Multiple Sclerosis (MS).

Before MS took my mother’s independence away, she was a very much the homemaker and loving mom. Her MS stripped away that independence though. First, she had trouble walking. Her eyes couldn’t focus on anything and her hands shook to the point that she couldn’t feed herself. She needed help getting out of bed, getting bathed, getting downstairs to the couch. If she went on her own she would sit on the floor and scoot to move inside the home. And at first there was no-one there for her except the kids.

There had been some trouble with her diagnosis at the start, and for a year or so she was trying to make lifestyle changes (like avoiding caffeine, or not eating certain foods) to remedy her imbalance and vision problems. As her condition progressed it was more evident that something wasn’t right. Her doctors in Alaska recommended that she go to better hospitals in Seattle, where she was diagnosed. She flew back east to participate in experimental treatments with ACTH, which helped restore some ability to walk. But MS takes ahold in a series of attacks and remissions, and her form was particularly aggressive. She returned and was wasting away from the disease.

My father spent most of his time at work or in the outdoors before my mother became seriously ill. It was only after her diagnosis that he took a desk job in Anchorage, an hour away from where we lived. He would get up at 4AM, travel to work, and be home between 4-5PM every day during the week, but would still disappear for the weekends with my brothers. I was left to watch my mother and two younger sisters and my older sister, who was “in charge” but couldn’t be relied upon. We didn’t know why she acted the way she did. She was angry and believed things that were obviously not true, but she was adamant and resistant and rebellious. She didn’t have a diagnosis at that point; instead she struggled with her reality and her family. We didn’t have a name for it, and it was only years later that we found a name: schizophrenia.

Part 2: Religion

Before her MS, religion was a part of my mother’s life that was a celebration and joy to see. Through all of our early travels as a family, wherever we landed she would find a local church to be part of. She was raised a Methodist in New England. When we lived in Minnesota we were part of Lutheran services there. When we moved to Petersburg we started at a Lutheran church, but were drawn to a new Assemblies of God that was starting because their song service was joyous, and my mother loved to sing. When we moved off the island in the Southeast to the mainland of Alaska, she found another Assembly of God. And then she became ill.

Church should be, above anything else, a community that draws together. Church should be a celebration and discipline of faith that is executed in practice. We are taught to seek humility, to make service, and uphold our ways. But church can be other things. It can be petty, and judgmental, and cliquish. It can be backward and superstitious. And it can be damning.

There is a practice in Pentecostal Charismatic churches of faith healing. If you’re not familiar with this, the idea is that your tribulations are all some sort of test that can be spiritually healed through acceptance of Christ. This typically means fervent prayer, and some laying on of hands. It’s the idea that belief in God’s power can heal you, based on your faith. But you have to be faithful, and you have to mean it. If God doesn’t heal you, it’s because you aren’t believing or confessing properly. This is an incredibly shitty concept to apply to someone diagnosed with a chronic, progressive disease.

My mother was a kind person, before all else. I will never remember her any other way than someone who walked into a room and made it brighter with her presence. She was educated and well-mannered. Before she was sick the worst thing she could say was “Lord love a duck” when she was angry. People were drawn to her.

After she became seriously ill, that changed. She lost her friends. At church we were told by the visiting faith healers that she was not accepting Christ into her heart if she could not be healed, and I could see that breaking her. We were not able to attend church regularly, and when we did it was painful to pass the tithing plate without contributing to it. We were poor, my mother was disabled, my father refused to attend any church, and it was obvious to them that we suffered only due to lack of faith.

Part 3: Secrets

My oldest sister had said a very long time ago that my mother had killed someone. I could not imagine what she meant or why she would say that, and I refused to repeat what she said. My sister was known to say things, after all. This wasn’t the first time an outlandish accusation had been laid by her.

At the same time, there was something about how my mother was so troubled by these ridiculous faith healers at church, and her desire to be healed. I wanted to attribute it to her faith, then I wanted to attribute it to her desire to be healed and truly live again. As her disease progressed there was a distance between my mother and father that was apparent. I think he felt hopeless and stuck, but loved her. I think she wanted him to be close when he couldn’t bring himself to be there for her.

Part 4: Ripples

At home I took care of my mother. I would get up in the mornings and help my mother get ready before carrying her downstairs to the living room, then get everybody out the door to get on the bus for school. If a note had to be written for one of the kids at school, I was the one who wrote it. When other kids played sports after school, I was heading home to take care of my mother. My oldest sister had graduated in 1980, before my mother became ill. She was supposed to stay home to help my mother during the day.

The day my oldest sister left home is like a scar in my memory. I was walking home, and was greeted by my two younger sisters who were running down the road to me. They were both crying and said that my oldest sister was killing our mother. I panicked and ran home in front of them. I entered through the back sliding doors of the house, and saw my sister positioned above my mother with her hand raised like she was going to hit her. My mother was lying on the floor, hands above her head and crying. There was blood on her head. I screamed.

My older sister had a panicked look. She turned and ran up into her room. My younger sisters and I picked up my mother and tried to console her as my older sister came back down. She had grabbed some personal belongings and was leaving as we yelled at her. None of us knew what had led up to the altercation. We focused on our mother but my older sister was gone. It would be days later that we found out she had called family back east and been provided a ticket to leave the state. It would be years later that I understood she was in psychosis that day, and would have no memory of what had taken place. It has taken a much longer time for me to forgive her for that.

It was after that when I became a primary caretaker for my mother. I was in my last year at school, and my grades were dropping because I had given up. The level of dysfunction at home was absurd. I was beginning to feel hopeless and angry.

My father had a regular habit of hitting me when he was angry. He would slap me, or hit me with a belt, or punch me when I made him upset. There was one night that my father was repeatedly hitting me in the kitchen and something inside just snapped, like I don’t have to just take this any longer. I wasn’t going to fight back, so I grabbed his hands and wouldn’t let go. I was angry, but just said “Stop hitting me!”. When he realized he couldn’t pull his hands away, I could see a change in his eyes. It was the last time that he hit me. I moved out shortly after. My younger sisters were old enough to take care of my mother, and I had to leave.

In 1988 my mother’s MS had progressed far enough that she wasn’t able to live at home anymore, and she moved to a full-time care facility. That was the same year that I left the state. I left to escape. I left to get out from under the care of my mother, and from my family, from religion, from a community I felt did not accept me. When she passed away in 2004 I wept unconsolably. There was regret, and guilt, and shame in what I had done by leaving.

Part 5: Reflections

It’s 2025 now. My parents have both passed away along with their siblings and family before them. My generation is now the oldest of the family, and there is time to look back. I was reminded this weekend of what my oldest sister had told me so many years ago, and I was reflecting on that and other thoughts. There was clear separation and distancing of my extended family. There was some unexplained vitriol between my aunt and my father that remained unresolved. There was the suffering that my mother went through with her fastidious devotion to religion, and how she dealt with her diagnosis with a sort of resigned acceptance. There was my father’s choice to distance himself from her. So much didn’t make sense.

I received an advert for a free weekend to look up newspaper articles using an online service. On Friday night I decided to go searching, and was finding old articles about the family. I started by looking for information about my wife’s family in the East Bay. She has a very lively family with all sorts of fun stories, and I was bolstering some family genealogy with what I found. One article in particular prompted the memory of my sister’s secret confession, so at 2AM I decided to start going down the rabbit hole.

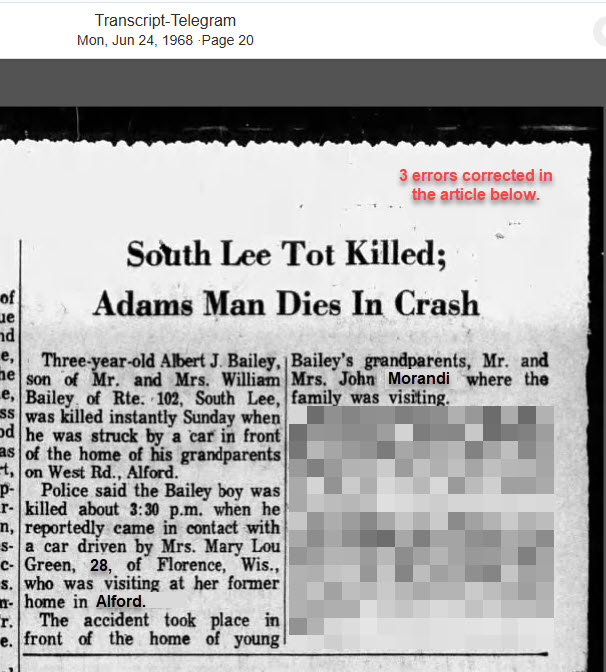

It took some time, but I found what I was looking for. The story was from 1968, when I was just eight months old. My older sister would have been just over six years old, which is likely old enough to remember a traumatic event. Besides the story my sister had told me, this had never been mentioned by my family. It crushed me to have found it.

There are several newspapers that carried the story, all repeated with the same errors in facts, which still reliably made the account of what took place. My parents were visiting my mother’s family. We were living in Florence, Wisconsin at the time and had driven out to Massachusetts – my father and mother, along with then 3 kids. Part of the story is unconfirmed – but it goes that my uncle (who loved cars) bought a green Ford Mustang. My mother and my grandmother took the car out to drive, so they ambled out the long road from my grandparent’s home, and turned onto the rural West Road. They had just started to drive down that road as they approached a neighbor’s residence. There were cars parked along the road, and from between some cars a 3 year old boy suddenly ran out and was struck by the car that my mother was driving. The boy was instantly killed. He was the grandson of the family who lived there. His parents had dropped him off at their home while they visited from a neighboring town. It was devastating.

My grandfather, and the child’s grandfather, were neighbors. They were both politically active and served together as Selectmen in their city. My mother was undoubtedly an acquaintance of their daughter, whose child had been killed. It was unfathomable to think this could happen, and yet it had. It irrevocably changed my mother, my parents, their system of support, and our lives afterwards. I hadn’t known it, but could see the ripples of tragedy that shaped our family.

My mother was the only child of four who had grandchildren. My mother’s older sister had died from Polio when she was just nine, so there were only three siblings in her family that grew to be adults. My grandparents were kind, but distant from us. My uncle was like my grandparents but died early from cancer in 1997. My mother’s sister was the longest lived and unrelenting in her animosity for my family. I think this partially explains the distance, and apparent abandonment felt on both sides.

Part 6: Summary

I think what bothers me most is how my mother persevered, and how this accident shaped her. She embraced religion and found comfort in it. If she had remained a Methodist or a Lutheran, the church may have consoled her for an unfortunate death of a child, and helped her come to some solace for her physical ailments. It was song service that brought her to the Assembly of God, but that church also chose to damn her with judgements of her faith and disregard her desire for forgiveness.

I wonder if we, the children, were considered some form of god’s retribution to my parents. I don’t know that they understood neuro-diversity at that time. There were programs coming in place in the early 70s to recognize and diagnose disability in schools that the older children weren’t able to take advantage of. I had a distinct sense growing up that we were a burden, especially from my father.

I can’t imagine how my mother lived with the trauma of a young child’s death, or how she perceived herself after that. I can’t imagine how my father decided to bottle everything up and distance himself from us. But it makes sense looking back, that this was what was happening.

I’m overwhelmed and reeling a bit to try to understand what impact this has had for four families. To the Bailey and Morandi families, my sincerest sadness and desire for peace to you. To the Chapin and Green families, understand what happened and know that there is healing in forgiveness and the passing of time.

It feels too late, but we can only start when we know.

References

- The Morning Union, June 24 1968, Page 6 (Springfield, MA)

- The Berkshire Eagle, June 24 1968, Page 14 (Pittsfield, MA)

- The North Adams Transcript, June 24 1968, Page 3 (North Adams, MA)

- The Transcript-Telegram, June 24 1968, Page 20 (Holyoke, MA)

Discover more from Utah House District 44

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.